(6 pm. – promoted by ek hornbeck)

Crossposted at Daily Kos and Docudharma

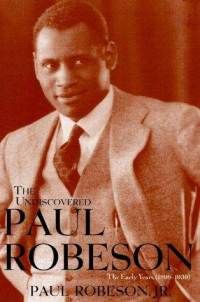

On January 23, 1976, one of the greatest Americans of the twentieth century died a nearly forgotten man in self-imposed seclusion in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

Over the last three decades or so, you rarely, if ever, hear his name mentioned in the popular media. Once every few years, you might hear someone on PBS or C-Span remember him fondly and explain as to why he was one of the more important figures of the past century. In many respects, he had as much moral authority as Nelson Mandela, Martin Luther King, Jr. and Rosa Parks; he was as politically active as Dick Gregory, Harry Belafonte, John Lewis, and Randall Robinson; and, as befits many men and women motivated by moral considerations, he conducted himself with great dignity. For much of his life, not surprisingly and not unlike many of his worthy successors, he was marginalized and shunned by the political establishment of his time — until events validated their ‘radical’ beliefs and resurrected their reputations.

Throughout his life, few principled men of his caliber paid as high a price and for as long a period as he did for his political beliefs.

|

|

|

|

:: ::

What did this man do that propel so many to ignore his numerous contributions and conveniently forget the crucial role he played in our culture and politics? Or, a few others to remember him with deep reverence and respect? Who was this brilliant man? This article best summarizes the depth and breadth of his accomplishments

|

How many people do you know who are athletes? How about an athlete who has won 15 varsity letters in four different sports? An athlete who has also played professional football while at the same time being valedictorian at his university? Does this athlete also hold a law degree? How many scholar-athlete performers can you name? Concert artists who have sold out shows around the world and who can perform in more than 25 different languages? Does this scholar-athlete-performer also act in Shakespearean and Broadway plays and in movies? Can you identify a scholar-athlete-performer who is also an activist for civil and human rights? Someone who petitioned the president of the United States of America for an anti-lynching law, promoted African self-rule, helped victims of the Spanish civil war, fought for India’s independence, and championed equality for all human beings? Did this scholar-athlete-performer-activist also have to endure terrorism, banned performances, racism, and discrimination throughout his career? Paul Robeson was all these things and more. He was the son of a former slave, born and raised during a period of segregation, lynching, and open racism. |

:: ::

I had been vaguely familiar with Robeson but first became fully aware of his accomplishments in some depth during an American/Cold War History seminar in undergrad school. One of the sections dealt with the famous 1948 Presidential Election. What caught my attention was not as much the dynamics of the Harry Truman-Tom Dewey race or the splintering of the Democratic Party by the defection of rightist Dixiecrats under Strom Thurmond but, rather, the leftist challenge to Truman’s candidacy by the Progressive Party and former Vice President under FDR, Henry Wallace.

Candidates on the Progressive Party’s ticket were the forerunners of today’s thousands of elected black officials not only in the South but all over the country (Paul Robeson: The Great Forerunner, p. 118). In the years to come, the critical role played by Robeson in campaigning for Wallace in the then-segregated states of the Deep South laid the foundations for African-Americans to re-enter national politics for the first time since Reconstruction.

|

Personally, he found in the newly established Progressive party a legitimate political organization through which to channel his reformist energies. As did millions of citizens, he rallied behind the Progressive candidate in the presidential elections of 1948, former Vice-President Henry Wallace. He appeared in Wallace campaign films. Robeson seemed genuinely inspired when, in a campaign speech in Washington, D.C., he told an audience, “We have taken the offensive against fascism! We will take the power from their hands and through our representatives we will direct the future destiny of our nation.” The least of Robeson’s postwar defeats was the dismal showing made by Wallace in the November elections. In a society now locked in a cold war with the Russian rival, Robeson’s progressive politics were labeled “communistic” and “treasonable.” He consistently suffered because of his outspoken political views. Speeches were abruptly canceled, concerts were called off, biographies of Robeson were banned from public libraries, and rioting often occurred during his appearances. (photo credit: The Paul Robeson Community Center) |

:: ::

|

|

|

|

:: ::

Robeson gave up pursuing a law career not long after graduating from Columbia Law School in 1923 when a white secretary in the Stotesbury and Milner law firm (where he worked) refused to take dictation from him. She told him, “I never take dictation from a ni***r.” Ambivalent about his future prospects as a black lawyer, Robeson had experienced considerable success in a parallel career path. He had made quite a name for himself in films, on stage, and in radio. The world order had been transformed after World War I and great social and cultural changes were underway. The Harlem Renaissance gained worldwide recognition for black entertainers and opened up opportunities for them in other countries. In the 1920’s, reviled in their own country, turned into outcasts, and treated worse than second class citizens in a segregated society, many black entertainers sought refuge in European countries to find acceptance abroad. Beginning in 1928, Robeson would spend over a decade living and performing not only in Great Britain but all over Europe. It was there that his popularity as an actor and singer grew by leaps and bounds.

Early on during his stay in London, several incidents happened which validated his decision to move abroad. In 1928, he became the first actor ever to be invited for lunch to the House of Commons by a group of Labour Party MP’s. In 1929, however, he was refused service at the world-famous Savoy Grill. In protest, Robeson wrote this letter to the Manchester Guardian on October 23, 1929

|

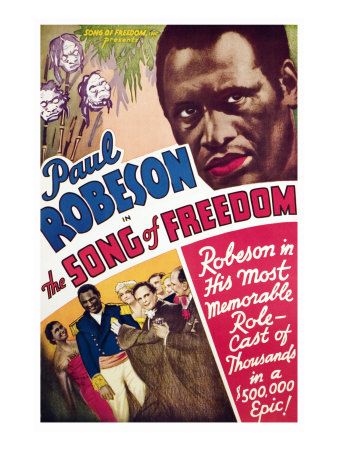

I thought that there was little prejudice against blacks in London or none but an experience my wife and I had recently has made me change my mind and to wonder, unhappily, whether or not things may become almost as bad for us here as they are in America. A few days ago a friend of mine invited my wife and myself to the Savoy grill room at midnight for a drink and a chat. On arriving the waiter, who knows me, informed me that he was sorry he could not allow me to enter the dining room. I was astonished and asked him why. I thought there must be some mistake. Both my wife and I had dined at the Savoy and in the grill room many times as guests. I sent for the manager, who came and informed me that I could not enter the grill room because I was a negro, and the management did not permit negroes to enter the rooms any longer. (A poster promoting Song of Freedom, a 1936 British film starring Paul Robeson, poster credit: Separate Cinema) |

Later, it was discovered that the hotel management had acted only after receiving complaints from American tourists who had been visiting London at the time. Because of Robeson’s letter to the Guardian and complaint to the then-British Prime Minister Ramsay MacDdonald (who condemned the incident), major hotels in London decided not to exclude blacks from among their patrons. In the late 1920’s, when lynchings of black men were still taking place in the Southern United States, it is not unrealistic to assume that what took place in London could not have conceivably happened in Robeson’s own country.

When Shakespeare’s Othello opened in London in 1930 with Robeson as the first black actor in 65 years to play the title role, he received 20 curtain calls on opening night. Whatever concerns his race might have raised soon dissipated for his magnificent, sophisticated, and mesmerizing performances defied the prevailing negative stereotypical image of the “uncultured and uncivilized” black man.

Living abroad and traveling extensively, Robeson — long interested in the issue of civil rights and workers rights — came into his own as his political activism grew.

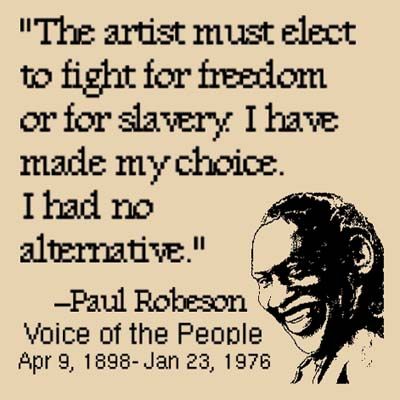

|

He was one of the top performers of his time, earning more money than many white entertainers. His concert career spanned the globe: Vienna, Prague, Budapest, Berlin, Paris, Amsterdam, London, Moscow, New York, and Nairobi. Robeson’s travels opened his awareness to the universality of human suffering and oppression. He began to use his rich bass voice to speak out for independence, freedom, and equality for all people. He believed that artists should use their talents and exposure to aid causes around the world. “The artist must elect to fight for freedom or slavery. I have made my choice,” he said. This philosophy drove Robeson to Spain during the civil war, to Africa to promote self-determination, to India to aid in the independence movement, to London to fight for labor rights, and to the Soviet Union to promote anti-fascism. It was in the Soviet Union where he felt that people were treated equally. He could eat in any restaurant and walk through the front doors of hotels, but in his own country he faced discrimination and racism everywhere he went. (Paul Robeson and his wife Eslanda Goode, sketch credit: Abraham Lincoln Brigade Archives) |

:: ::

With the outbreak of World War II in 1939, Robeson returned to the United States. Years later, he said, “I learned my militancy and my politics, from your Labor Movement here in Britain…. That was how I realized that the fight of my Negro people in America and the fight of oppressed workers everywhere was the same struggle.” More importantly, living in England had solidified his commitment to the sufferings of the poor and oppressed. It was as if he had found his purpose in life.

Upon his return, Robeson’s political activities grew on behalf of labor unions and many minority groups. Fervently anti-Fascist, he was also an initial opponent of American involvement in World War II but he supported the war effort with a great deal of enthusiasm once Germany attacked the Soviet Union in June 1941. His acting and singing career blossomed and soon he was one of the most recognizable entertainers in the country. Robeson’s demands for racial justice both at home and abroad also would gain him many enemies.

By the late 1940’s, the domestic political environment was also about to dramatically change for Robeson with the onset of the Cold War, growing concerns about the perceived external and internal threats posed by Communism, and the beginning of the paranoid McCarthy Era during which loyalties of millions of Americans were openly questioned. A concert to benefit the Civil Rights Congress at Peekskill, New York in 1949 resulted in a riot and contributed significantly, if unfairly, in him becoming the target of militant ant-communists. Robeson was not injured during the riot that ensued

|

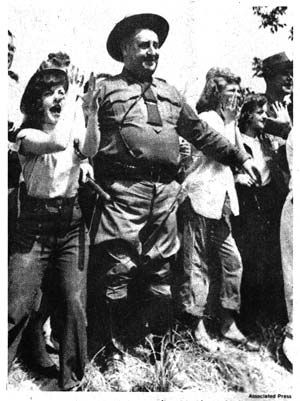

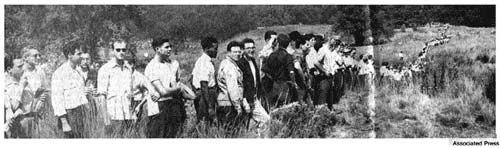

In 1949 Robeson embarked on a European tour and in doing so spoke out against the discrimination and injustices that blacks in American had to confront. His statements were distorted as they were dispatched back to the United States. Although Robeson got mixed responses from the black community, the backlash from whites culminated in riot before a scheduled concert in Peekskill, New York, on August 27, 1949; a demonstration by veteran organizations turned into a full-blown riot. Robeson was advised of this and returned to New York. He did agree to do a second concert on September 4 in Peekskill for the people who truly wanted to hear him. The concert did take place but afterwards a riot broke out which lasted into the night leaving over 140 persons seriously injured. With such violence surrounding Robeson’s concerts, many groups and sponsors no longer supported him. (Demonstrators jeering people arriving for Robeson’s concert, photo credit: Reporter Dispatch, White Plains, NY) :: ::

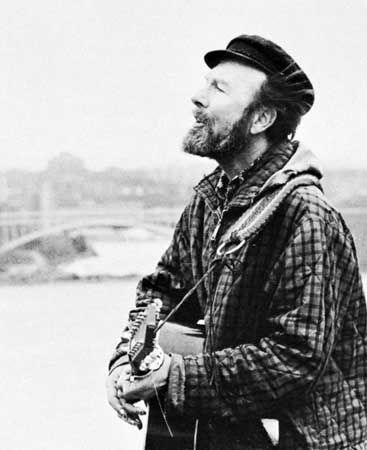

:: :: Pete Seeger was to perform at the concert, along with several folk singers and musicians, before Robeson appeared. Seeger arrived early, at 11 a.m. The line of 2,500 union members was forming around the field like a human wall… “It may sound silly now, but we were confident law and order would prevail,” said Seeger in an interview. “I had been hit with eggs in North Carolina, Alabama and Mississippi, but this was New York State. “We heard about 150 people standing around the gate shout things like ‘Go back to Russia! Kikes! Ni**er-lovers!’ It was a typical KKK crowd, without bedsheets,” Seeger said.

The police confiscated some baseball bats from the concert guards, and prevented a few clashes during the concert, which went on peacefully. Seeger sang folk songs, playing his banjo, and the program ranged through Mozart and Handel before Robeson came on… Seeger left the concert grounds with his wife and children, his wife’s father and another couple. One of the concert guards told them to roll up their windows. A policeman in the road waved them south toward Peekskill. Around the corner was a man standing next to an immense pile of baseball-sized rocks. He took aim and hit the Seegers’ car. The stones came faster, and Seeger told everybody to get down. The windows smashed inward. A woman in the car was hit. Danny Seeger, 2, was huddled under the Jeep seat. He was covered with glass… South of Peekskill, the rock-throwing continued through Buchanan, Montrose and Croton along Route 9 as the smashed and dented cars and buses headed back to New York City. (photo credit and excerpt from The Robeson Riots of 1949 by Steve Courtney of the Reporter Dispatch, White Plains, NY) :: ::

|

:: ::

|

|

|

|

:: ::

Robeson was not a perfect human being. Though never a member of the Communist Party of the United States, his admiration of the Soviet Union was the direct cause of some of his troubles with rightist elements in this country. Such was the price paid by many political activists caught in the cross currents of Cold War politics. It is important to note that the J. Edgar Hoover-led FBI maintained a large dossier on him and his wife for over three decades starting in 1941 — well before the Cold War had started and during the World War II years through 1945, a period during which the USSR was officially an ally of the United States. If you are familiar (as I am) with the leading American press publications — and particularly leftist newspapers and magazines like PM, Daily Worker, and the New Leader — of the 1941-1945 period, you know well that stories about the “heroism” of Soviet soldiers fighting the Nazi war machine were as common in that day as are escapades of Paris Hilton and Lindsey Lohan in today’s newspapers.

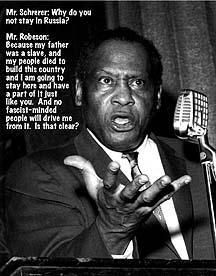

Accused of being a Communist by his many critics and refusing to sign an affidavit to validate this charge, Robeson was called to testify before the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) on June 12, 1956. To say that he held ultra-nationalists members of this committee in low regard is to grossly understate the contempt he had for them. During his testimony, he was constantly badgered in the “America, love or or leave it” manner reminiscent of contentious debates a decade later during the Vietnam War.

Here are a few excerpts from his testimony before HUAC in exchanges with the Committee Chairman Francis Walter (D-PA), Congressman Gordon Scherer (R-OH), and HUAC Counsel Richard Arens, an aide to Senator Joe McCarthy (R-WI).

|

THE CHAIRMAN: Proceed… Mr. ROBESON: Could I say that the reason that I am here today, you know, from the mouth of the State Department itself, is: I should not be allowed to travel because I have struggled for years for the independence of the colonial peoples of Africa. For many years I have so labored and I can say modestly that my name is very much honored all over Africa, in my struggles for their independence. That is the kind of independence like Sukarno got in Indonesia. Unless we are double-talking, then these efforts in the interest of Africa would be in the same context. The other reason that I am here today, again from the State Department and from the court record of the court of appeals, is that when I am abroad I speak out against the injustices against the Negro people of this land. I sent a message to the Bandung Conference and so forth. That is why I am here. This is the basis, and I am not being tried for whether I am a Communist, I am being tried for fighting for the rights of my people, who are still second-class citizens in this United States of America. My mother was born in your state, Mr. Walter, and my mother was a Quaker, and my ancestors in the time of Washington baked bread for George Washington’s troops when they crossed the Delaware, and my own father was a slave. I stand here struggling for the rights of my people to be full citizens in this country. And they are not. They are not in Mississippi. And they are not in Montgomery, Alabama. And they are not in Washington. They are nowhere, and that is why I am here today. You want to shut up every Negro who has the courage to stand up and fight for the rights of his people, for the rights of workers, and I have been on many a picket line for the steelworkers too. And that is why I am here today… :: ::

Mr. ROBESON: In Russia I felt for the first time like a full human being. No color prejudice like in Mississippi, no color prejudice like in Washington. It was the first time I felt like a human being. Where I did not feel the pressure of color as I feel (it) in this Committee today. Mr. SCHERER: Why do you not stay in Russia? Mr. ROBESON: Because my father was a slave, and my people died to build this country, and I am going to stay here, and have a part of it just like you. And no Fascist-minded people will drive me from it. Is that clear? I am for peace with the Soviet Union, and I am for peace with China, and I am not for peace or friendship with the Fascist Franco, and I am not for peace with Fascist Nazi Germans. I am for peace with decent people. Mr. SCHERER: You are here because you are promoting the Communist cause. Mr. ROBESON: I am here because I am opposing the neo-Fascist cause which I see arising in these committees. You are like the Alien (and) Sedition Act, and Jefferson could be sitting here, and Frederick Douglass could be sitting here, and Eugene Debs could be here. (Paul Robeson Shouts Down HUAC, photo credit: The Cultural Worker) :: :: THE CHAIRMAN: There was no prejudice against you. Why did you not send your son to Rutgers? Mr. ROBESON: Just a moment. This is something that I challenge very deeply, and very sincerely: that the success of a few Negroes, including myself or Jackie Robinson can make up – and here is a study from Columbia University – for seven hundred dollars a year for thousands of Negro families in the South. My father was a slave, and I have cousins who are sharecroppers, and I do not see my success in terms of myself. That is the reason my own success has not meant what it should mean: I have sacrificed literally hundreds of thousands, if not millions, of dollars for what I believe in… :: :: Mr. ARENS: Now I would invite your attention, if you please, to the Daily Worker of June 29, 1949, with reference to a get-together with you and Ben Davis. Do you know Ben Davis?… Mr. ROBESON: I say that he is as patriotic an American as there can be, and you gentlemen belong with the Alien and Sedition Acts, and you are the nonpatriots, and you are the un-Americans, and you ought to be ashamed of yourselves. :: :: |

:: ::

If you are largely unfamiliar with the early influences upon Robeson, watch this video — Paul Robeson – Renaissance Man — which summarizes details of his attraction to socialism after first meeting George Bernard Shaw during the decade he spent living in England from 1928-1939. While largely free of racism, British society was hardly a paradise for men of color. The video also explains the depths of independence struggles in Africa and the pernicious effects of imperialism that Robeson learned about from many future leaders. Interspersed with many clips of his movies and singing, you will hear remarks by Tony Benn, Harry Belafonte, Jr., and others of Robeson’s perceptions about pre-World War II white liberalism and its many contradictions.

British Statesman Lord Palmerston once observed that nations do not have permanent allies or friends. They only have permanent interests. And as any student of international relations and history knows, once political “marriages of convenience” are over, the consequences are very unpredictable. Some societies adjust well to the divorce; others never quite recover from the shock. Individuals caught in this ever-changing dance of statecraft also have to learn to adjust to the cynical realism of world politics. In this one instance, it is fair to say that Robeson was a slow learner.

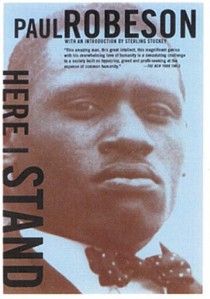

He was also, however, by anyone’s fair and unbiased definition, a great American and one who dared to confront the societal injustices and political contradictions firmly entrenched in his own country’s long traditions. Borrowing the title from Martin Luther’s 1521 ‘Here I Stand’ Speech before the Diet of Worms in Germany, he stood up to express his outrage in his autobiography published in Great Britain during an earlier infamous ‘You-Are-With-Us-Or-Against-Us’ Era when he had much to lose in terms of both fame and fortune. This is what gained him, as we say in today’s parlance, “moral authority” and “political stature” — even if just about everyone in the mainstream media failed to recognize it at the time

|

In one area the boycott achieved a near-total success: with one insignificant exception, no white commercial newspaper or magazine in the entire country so much as mentioned Robeson’s book. Leading papers in the field of literary coverage, like The New York Times and the Herald-Tribune, not only did not review it; they refused even to include its name in their lists of “books out today.” |

:: ::

|

|

|

|

:: ::

How does Robeson compare to several other prominent African-Americans who followed him and are celebrated today for their ground-breaking achievements? Quite well, actually. If he had done nothing else except excel academically at Rutgers University and graduated from Columbia University Law School — where future US Supreme Court Justice, William O. Douglas, was a classmate — undoubtedly he would have had a very comfortable and successful life. Considering that he finished law school in 1923, this was quite an achievement in those days.

A decade before the Reverend Martin Luther King, Jr. and Rosa Parks (deservedly) emerged as the face of the modern civil rights movement — one identified with fighting Jim Crow laws largely in the South — Robeson had been an important participant in a long civil right struggle centered in New York City. Additionally, many historians credit him for sowing the seeds of the political movement to come during the 1948 Wallace Presidential Campaign. He had tirelessly championed the cause of poor and oppressed people not only in the United States but all over the world. If he was a beloved figure for Welsh coalminers in Great Britain, in Africa he had achieved near-mythical status for his anti-colonialist positions. (sketch credit: The City Project)

One example of his political activism: as this diary — Labor Organizer Joe Hill: Executed This Day in 1915 — first mentioned it a few years ago, you can listen to the Depression-era ballad, ‘I Dreamed I Saw Joe Hill Last Night’ as sung by Robeson in this video. The scenes are from a 1998 protest in New York City against then-Mayor Rudy Giuliani (R-NY).

|

I Dreamed I Saw Joe Hill Last Night I dreamed I saw Joe Hill last night, “In Salt Lake, Joe,” says I to him, From San Diego up to Maine, |

:: ::

In the field of professional sports, decades before Joe Louis, Jackie Robinson, Bill Russell, and Jim Brown came to dominate their respective sports (boxing, baseball, basketball, and football), Robeson had been an All-American football player at Rutgers University and, following that, one who also played pro football. In the arts — well before Singer Sammy Davis, Jr. and Actor Sidney Poitier became ‘acceptable’ to mainstream white audiences — Robeson was a respected and accomplished stage/film actor and singer with numerous recordings, the most famous of which is perhaps this 1928 rendition of Ol’ Man River.

And, yes, before anyone had ever heard the fiery speeches of Malcolm X and the morally courageous anti-war stands taken by Muhammad Ali in the 1960’s, Robeson had carved a niche for himself not only as an anti-imperialist champion but, also, as a forceful advocate for economic and social justice.

It would, therefore, not be too much of a stretch to assert that in many different fields of endeavor, Robeson was an unique individual way ahead of his time.

:: ::

What accounted for his greatness and what were the reasons so many ‘feared’ him? As the 1999 PBS ‘American Masters’ program, Paul Robeson: Here I Stand, described it

|

Paul Robeson was the epitome of the 20th-century Renaissance man. He was an exceptional athlete, actor, singer, cultural scholar, author, and political activist. His talents made him a revered man of his time, yet his radical political beliefs all but erased him from popular history. Today, more than one hundred years after his birth, Robeson is just beginning to receive the credit he is due. During the 1940s, Robeson’s black nationalist and anti-colonialist activities brought him to the attention of Senator Joseph McCarthy. Despite his contributions as an entertainer to the Allied forces during World War II, Robeson was singled out as a major threat to American democracy. Every attempt was made to silence and discredit him, and in 1950 the persecution reached a climax when his passport was revoked. He could no longer travel abroad to perform, and his career was stifled. Of this time, Lloyd Brown, a writer and long-time colleague of Robeson, states: “Paul Robeson was the most persecuted, the most ostracized, the most condemned black man in America, then or ever.” |

:: ::

I have long admired Robeson for his staunch political convictions, principled stands, and perseverance when the odds were heavily stacked against him. That is the essence of political courage and greatness. But, in the “fierce urgency of now” and this obsessively politically correct era we live in, we tend to forget many like him who’ve come before us — especially those unfairly tarred with accusations of unpatriotic behavior by shameless demagogues amongst our midst

|

To this day, Paul Robeson’s many accomplishments remain obscured by the propaganda of those who tirelessly dogged him throughout his life. His role in the history of civil rights and as a spokesperson for the oppressed of other nations remains relatively unknown. In 1995, more than seventy-five years after graduating from Rutgers, his athletic achievements were finally recognized with his posthumous entry into the College Football Hall of Fame. Though a handful of movies and recordings are still available, they are a sad testament to one of the greatest Americans of the twentieth century. If we are to remember Paul Robeson for anything, it should be for the courage and the dignity with which he struggled for his own personal voice and for the rights of all people. Note: if you’ve never watched ‘Here I Stand’ on PBS, learn more about the program. The above video shows his son Paul Robeson, Jr. discuss baseball great Jackie Robinson’s testimony before the House Un-American Activities Committee and what both his father (at the time) and Robinson really felt about this appearance many years later. |

:: ::

|

|

|

|

:: ::

Towards the end of Arthur Miller’s classic play, Death of a Salesman, Linda Loman cries out with a memorable demand for respect for her deceased husband, Willy Loman

|

Attention, attention must finally be paid to such a person. You called him crazy… no, a lot of people think he’s lost his… balance… How long can that go on? How long? You see what I’m sitting here and waiting for? And you tell me he has no character? The man who never worked a day but for your benefit? When does he get the medal for that? |

The painful question implicit in Linda Loman’s anguished cry for help is, at least to me, quite self-evident: what kind of a society do we live in, one that recognizes and acknowledges a man’s contribution to his fellow human beings only after he has departed this earth and left us for good? And even then, we often fail to credit those whose shoulders we stand upon today. For, without their efforts and sacrifices, we wouldn’t amount to much.

Indeed, not unlike Willy Loman, attention must be paid to Paul Robeson.

:: ::

A Note About the Diary Poll

|

|

|

|

:: ::

Simply stated, the McCarthy Era was one of the most disgraceful periods in 20th century American history. An air of suspicion hung over ordinary citizens if they were suspected of not conforming to the government’s interpretation of being a “good” American. Several millions people underwent investigation by federal authorities until Senator Joe McCarthy was censured by the United States Senate. He died a broken man a few years later.

“Guilty until found innocent” was often the approach used by investigators to tar many Americans with wild, unproven allegations of consorting with the enemy. Loyalties were questioned, reputations tarnished, careers destroyed, families uprooted, and lives ruined. Many notable Americans from the entertainment industry were put on lists which made their lives miserable

|

During the Cold War era, the House Committee on Un-American Activities (HUAC) interrogated more than 3,000 government officials, labor union leaders, teachers, journalists, entertainers, and others. They wanted to purge Communists, former Communists, and “fellow travelers” who refused to renounce their past and inform on associates from positions of influence within American society. Among the Committee’s targets were performers at events held in support of suspect organizations. |

To understand the effects that the Committee On Un-American Activities (HUAC) had on American society, I would urge you to see this chilling documentary film made by Radical Films in 1962 by a private citizen challenging the government’s heavy-handed and, often, illegal methods. It covers the history of HUAC investigations from 1932 onwards, including those of the Hollywood Ten and others put on lists like the Red Channels List. It also includes extensive 1960 footage of the San Francisco City hall police water hosing protesters.

The language used in this documentary will remind you of hateful, violent, and nationalistic rhetoric used by many on the political right in recent decades. Where do you think today’s Teabaggers get their talking points from? It comes from decades of engaging in conspiracy theories and imagined threats to the “American way of life.” This feeling of paranoia and victimization persists to this day amongst many conservatives.

If time permits, do watch the full video and remember to take the diary poll.

:: ::

4 comments

Skip to comment form

Author

… linguist, activist, and more. As this 1943 editorial cartoon shows, Paul Robeson was called the “20th Century’s Greatest Renaissance Man.”

Charles H. Alston (1943), National Archives and Records Administration

During a week when we just celebrated Martin Luther King Day and the long struggle that led to the Voting Rights and Civil Rights Acts of the mid-1960’s, Robeson deserves to be remembered. In today’s national political environment — when so many of us are enamored only with the breaking news of the day or, obsessed with the minutiae of this or that political development or, disheartened by the real (or perceived) inadequacies of our political leaders — Paul Robeson stands tall as a symbol of integrity.

His life’s struggle is an example of eventual vindication through principled behavior. Even if some of us don’t know it, we owe him a great deal.

:: ::

You can help in many ways by exploring and supporting the Bay Area Paul Robeson Centennial Committee’s website

Tips and the like here. Thanks.

Author

… photographs, sketches, and a few editorial cartoons from the 1950’s in the version I posted over at Daily Kos.

Take a look at the many wonderful comments in which several people recounted their own — or their family’s — memories of Paul Robeson.

Author

… for promoting this diary. Here’s Paul Robeson in California in 1942.

Here He Stands – Paul Robeson leading Moore Shipyard workers in Oakland, CA

in singing The Star-Spangled Banner, September 1942